CHRISTINE BERNSTED

DENMARK

1st PRIZE

EDWARD WALTON

AUSTRALIA

HANS REINER STORZ

MEMORIAL AWARD

ANNA DOROTHEA MUTTERER

GERMANY

BISHOP INSTRUMENTS

AND BOW AWARDS

CHRISTINE BERNSTED

DENMARK

1st PRIZE

EDWARD WALTON

AUSTRALIA

HANS REINER STORZ

MEMORIAL AWARD

ANNA DOROTHEA MUTTERER

GERMANY

BISHOP INSTRUMENTS

AND BOW AWARDS

Melbourne International

Violin Competition

SPONSORED BY JENNEN

Music competitions come in many sizes, although their shapes are pretty much the same throughout the world. If you win, there’s a prize at the end – cash or prestige; both, if you’re lucky. But the format is an inevitable one: you apply by sending in a sample of your work, you go through the (usually) impersonal process of being assessed remotely, you get chosen as a candidate, you go through an elimination round or a set of finals, and – if you last the distance – you get to perform live in front of a panel of judges.

As a general rule, the more well-known the prize, the larger the reward; more so if a benevolent government takes an interest and puts some money where its cultural mouth is. For this newest kid on the block, initiated by young Melbourne musician and entrepreneur Jennen Ngiau-Keng, the cash rewards are modest – $5,000 for First Prize, and $1,000 each for silver and bronze places. But it’s hard to imagine a more daunting end-of the-road process for the three finalists.

First, the competition has set its focus on a dominant figure in Western music: Johann Sebastian Bach. Second, if you confine yourself to this composer, then you’re talking exclusively about his Six Sonatas and Partitas – music of matchless craft and integrity but extra-demanding because the violinist plays solo; no distracting orchestra or helpful piano accompanist.

Third, the jury comprises a collection of Melbourne’s professional musicians – no bureaucrats, no music-world politicians, all present or past professionals, and all without an axe to grind or a student to promote.

I don’t care how familiar, even blasé you may be with playing in front of a jury, or how many competitions and concours you have fronted throughout your career: this one is very demanding.

But the three picked out for the finals – Christine Bernsted from Denmark, Anna Dorothea Mutter from Germany, and Australian Edward Walton – faced further hurdles.

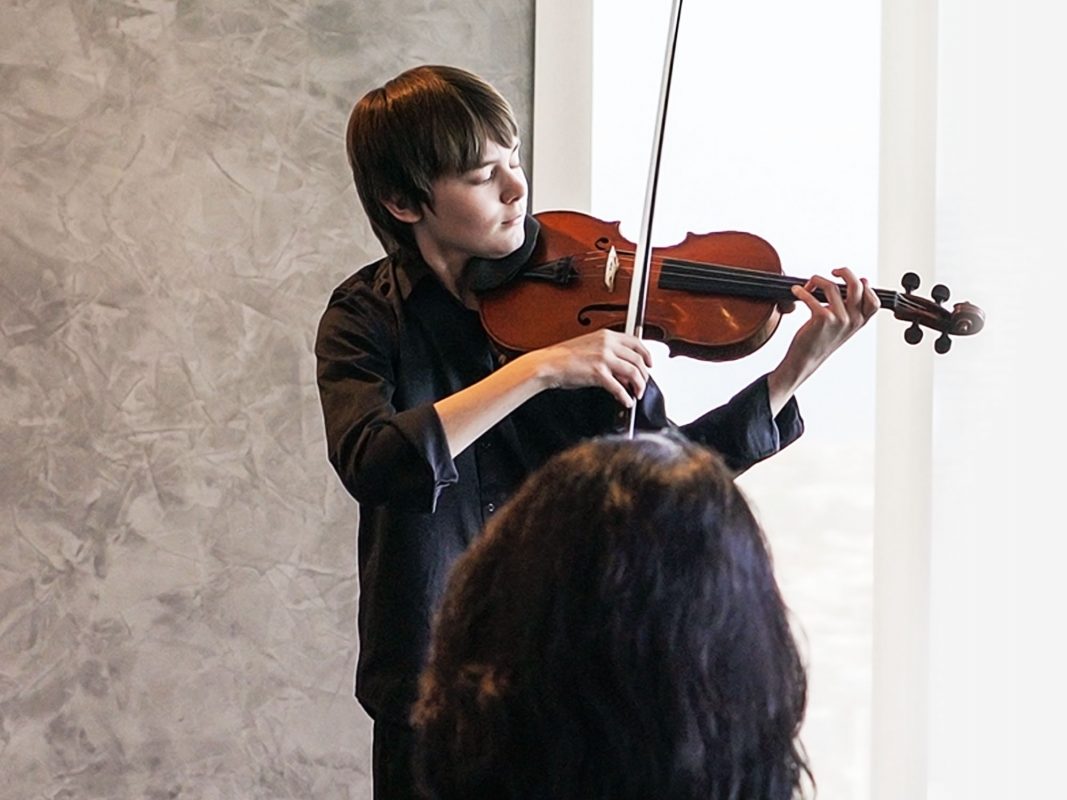

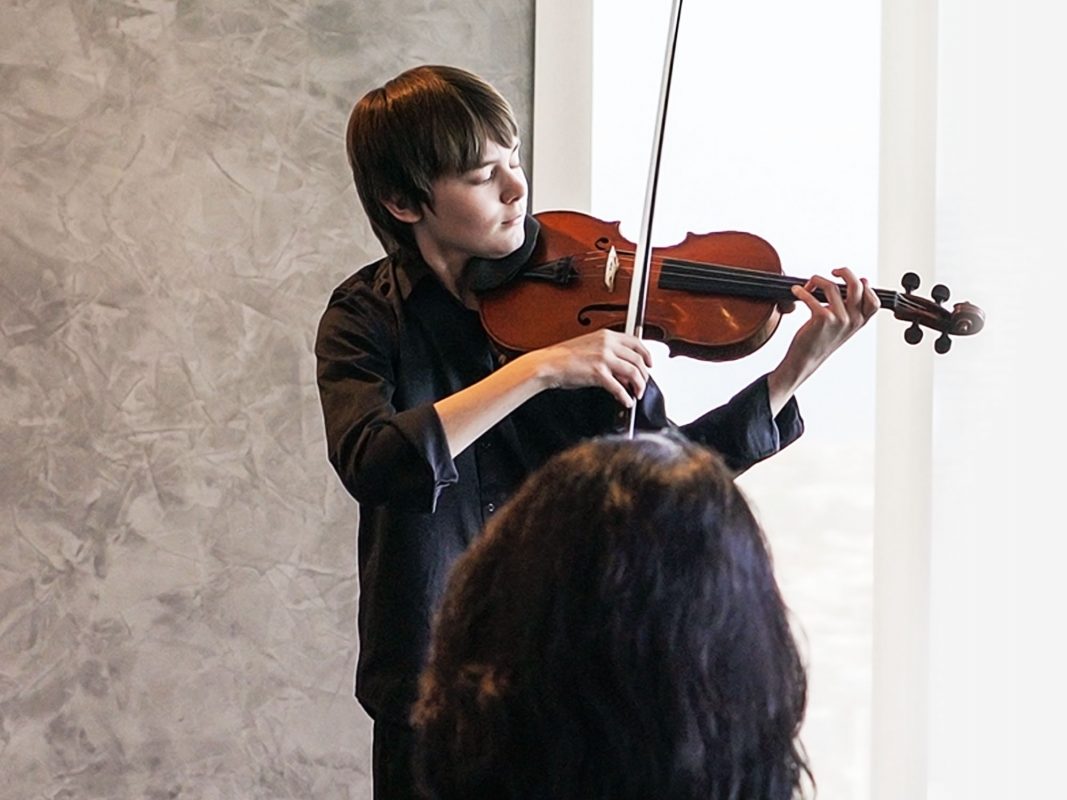

Edward Walton showed his fluent finger-work right from the opening Preludio of the E Major Partita and found a happy dynamic level on which to operate, moving effortlessly from the rapid-fire opening, through the familiar Gavotte en rondeau and into the lightly bounding Gigue finale. This player’s hallmark is an apparent absence of stress as he sailed through many taxing pages with unflappable assurance.

Obviously, the market for such an event is promising but the organizers – Jennen Ngiau-Keng, founder of JENNEN Shoes, and Alfred Hornung, CEO of Tingleman Print Media Group and a former cellist with a formidable Bach background – can use help from sponsors with an eye to quality. As well, you can see that, after a few years, the competition’s current all-Bach diet could prove difficult to sustain; still, the repertoire for solo violin holds some comparable, if later, masterworks.

Finally, the enterprise needs to expand physically so that a larger audience than just jurors and devoted family-members can experience this riveting art-form which is both concentrated and engrossing. Obviously, the event has the goodwill of top-class Melbourne musicians, happy at Ngiau-Keng’s initiative and pleased to be involved in its

processes. What is needed now is a bigger platform: more public awareness, a wider

operational base, larger accommodations. Sunday’s success should serve as a vigorous reinforcement of the competition’s potential.

Press release by Clive O’Connell.

Melbourne International Violin Competition

sponsored by JENNEN

One after the other, these three young violinists performed a partita – the voluble No. 2 in D minor from Bernsted and Mutterer, the more flighty No. 3 in E from Watson – in a moderate boardroom – sized space, with only a few metres at most between musician and front row. No room for hiding anything here: every sound came across with immediate impact, any slight deviation instantly apparent.

Obviously, the market for such an event is promising but the organizers – Jennen Ngiau-Keng, founder of JENNEN Shoes, and Alfred Hornung, CEO of Tingleman Print Media Group and a former cellist with a formidable Bach background – can use help from sponsors with an eye to quality. As well, you can see that, after a few years, the competition’s current all-Bach diet could prove difficult to sustain; still, the repertoire for solo violin holds some comparable, if later, masterworks.

Finally, the enterprise needs to expand physically so that a larger audience than just jurors and devoted family-members can experience this riveting art-form which is both concentrated and engrossing. Obviously, the event has the goodwill of top-class Melbourne musicians, happy at Jennen Ngiau-Keng’s initiative and pleased to be involved in its processes. What is needed now is a bigger platform: more public awareness, a wider operational base, larger accommodations. Sunday’s success should serve as a vigorous reinforcement of the competition’s potential.

Press release by Clive O’Connell.